Encontrei no YouTube, este quatro vídeos captados nos bastidores e durante os vários ensaios da ópera de Rossini "Le Comte Ory" apresentada no Teatro Regio di Torino em 1999.

Fazem parte do elenco, entre outros:

Rockwell Blake

Alexadrina Pendatchanska

Michele Pertusi

Alessandro Corbelli

O maestro é Bruno Campanella

Curiosa é a comparação com a ópera Il Viaggio à Reims (Samuel Ramey, Ruggero Raimondi).

Aqui ficam os "links" para os vídeos

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N1V99NyVz1o

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CiOjSy6ZHQM

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VSSDA37shBQ

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EeQJ4SnPpl0

Tuesday, July 22, 2008

Monday, July 21, 2008

Mariella Devia

Mariella Devia, soprano italiano. Canta exclusivamente na Europa.

Aos 60 anos interpreta, assim, La Travita de Verdi

Aos 60 anos interpreta, assim, La Travita de Verdi

Saturday, July 19, 2008

Joan Sutherland já está a recuperar

Li aqui que o soprano já se encontra em recuperação.

As melhoras Dame Joan.

As melhoras Dame Joan.

Monday, July 14, 2008

Friday, July 11, 2008

Julia Lezhneva - Um nome a reter

Descobri há relativamente pouco tempo a voz de Julia Lezhneva soprano russo que com apenas 18 anos (2007) faz o que se segue...

Reparem só na cara de espanto da Teresa Berganza.

Uma promessa, de facto.

Reparem só na cara de espanto da Teresa Berganza.

Uma promessa, de facto.

Thursday, July 10, 2008

Elinor Ross

Descobri a a voz de Elinor Ross por mero acaso, numa das minhas longas e frequentes deambulações pelo youtube.

Descobri a a voz de Elinor Ross por mero acaso, numa das minhas longas e frequentes deambulações pelo youtube.Descobri-a numa gravação da Norma ocorrida em 1967 em Berlin.

Curiosamente num artigo da Opera News verifique que Scott Barnes, antes de fazer uma entrevista ao soprano, tinha também descoberto no youtube excertos dessa gravação.

Aqui fica o artigo da Opera News e alguns vídeos do youtube com a Norma de Berlim que conta também com a presença de Mario del Mónaco.

About a week before I was to interview former Met soprano Elinor Ross, I was surfing YouTube and discovered that someone had just uploaded selections from a 1967 Berlin production of Norma, featuring Ross and Mario del Monaco. Granted, the black-and-white camerawork was nothing fancy, and the sets, costumes and acting were, to be kind, "of the period."

But the beautiful, cavernous, overtone-laden sound that came out of Ross was overwhelming. The dynamic and emotional range, from tenderness to ferocity, the clarity of coloratura and the sheer immensity and beauty of her voice amazed me. I had always considered Ross a utility singer — one that the Met could summon on a moment's notice, whose performances of Verdi and Puccini would satisfy if not delight the knowledgeable Met audience. The video proved that she was much, much more than that. And her life, as I was soon to discover, could easily have earned her a medal for endurance.

"Hi, darlin'," says Ross as she opens the door to let me in. "I have to warn you, I'm a talker!" Her apartment, with spectacular views of Manhattan, is painted a pale lemon yellow. Clearly, color is very important to her — not just in the furnishings and artwork she has chosen but in the way she dresses. She moves slowly, and there is a walker nearby, but neither the apartment nor the woman has the look of living in the past.

Born in Tampa, Florida, in 1930, Ross attended Syracuse University. She came to New York shortly thereafter, studying with William Herman, famous for being the teacher of Roberta Peters. She also studied with Stanley Sontag and coached with Leo Resnick. Her professional debut came in 1958 with Cincinnati Opera, as Leonora in Il Trovatore. She was soon performing with many U.S. companies, including San Francisco, Chicago and Boston. But the skill to do the work and the skill to get the work are very different things. Although she appears to be very outgoing and sure of herself, Ross claims to be quite shy. "I could never go into a crowd and push myself. I couldn't talk about myself to an agent or a manager. I was with Sol Hurok, but he said I needed experience, so he sent an agent with me to Italy. At Verona, I had the greatest response in the world. I had a bis [encore] every time I opened my mouth. But Leyla Gencer's boyfriend was running the whole operation, and she and I did the same roles. So when it was the season, she got the roles, and I didn't get called back. I filled in for her as Aida, and I had to bis both the arias. Amazing success, and I didn't go back!

"Tom Schippers took me to Scala to understudy Callas in Medea. I figured it was good experience, and I needed the money, so I did all the rehearsals, and she came back and canceled my performance. She paid off the whole orchestra, the chorus, even me! The whole house was dark, because she didn't want me to sing in her stead. We actually became friends, because I was this little nothing, and we spoke all the time. As a young singer, there was nothing to be done. I wanted to sing leading roles in leading houses, and I did."

Our conversation turns to the 1967 Norma preserved on that YouTube video. "My son had just said, 'Mom, it's too bad you don't have any videos out.' I remembered in Germany we were put on TV. We didn't sign anything or have very much notice. There were just big TV cameras at one performance. Well, my son e-mailed the theater in Berlin, and they said it was in the archives. Then three weeks later, all this stuff started appearing on YouTube. Someone just sent me a whole DVD. I thought it was with Cossotto, since I did a lot of Normas with Fiorenza, but it was a gal I don't really much remember [Giovanna Vighi]. I never kept score of anything I was doing. I was busy running around from here to there, and then of course the sicknesses. When I made my 1970 Scala debut in Cavalleria Rusticana, my husband [attorney Jerome Lewis] was dying. They told him not to come, that the plane's pressurized cabin would kill him. He came anyway but never got to see me at La Scala. I had to cancel my engagement with Vienna Staatsoper and become his cook and nurse. He was in an Italian hospital for six weeks, until I could bribe an airline to get him to the States."

Ross returned to New York on a Tuesday, and the following day, the Met called her manager, Herbert Barrett, asking her to make her debut that Saturday — June 6, 1970 — singing Turandot, a role she would sing sixteen times with the company. It was a daunting challenge, since she had just come from weeks of singing Santuzza, a different type of role centered in a different part of her voice. "The thing about Turandot is, you can either do it, or you can't," says Ross. "I had a big voice with lots of high notes, and I had done the role before. I got a costume fitting but no stage rehearsals. Pilar Lorengar was my Liù, and Corelli didn't come to either of my music rehearsals. My friends Nedda Casei and Shirley Love kept my husband on the phone from backstage during the performance and gave him the blow by blow. During the three questions, Corelli turned his back to the audience to face me and put his hand down his pants. I didn't know what the hell was going on. I didn't know where to look, or what was gonna happen. He brought a wet sponge out and put it in his mouth. He had wet sponges all over the stage!"

The public never knew that Ross's husband died following open-heart surgery (still in its experimental stages) shortly thereafter. Ross had to work and simply jumped right back in, singing Ballos and filling in for Régine Crespin in a string of Met Toscas with Carlo Bergonzi. "When I think of the things I did — I must have been crazy," she says. "But I had responsibilities — I had to pay for the household."

Following the death of her husband, Ross gave up the bulk of her international travel to be near her son. "He was going through a lot of things," Ross recalls. "His father and grandfather had died, he was a teenager, he was gay, and I wanted him to be proud of who he was, because that's the only 'you' you get to be in this lifetime. I did the things that I thought were right. I didn't get the career to where I thought it was going to go, but that's life. I started covering more at the Met. I never had rehearsals — I got thrown on, and every time was like a debut. That was tough. I loved doing Gioconda, but [Giuseppe] Patanè didn't like me, and I couldn't stand him. I like most people, but he struck a chord in me. Anyway, he walked out when he heard that I was replacing in that famous Trovatore."

The "famous" Trovatore, in 1978, involved more twists than most pulp fiction: Ross, fighting her weight, had put herself on the faddish water diet. A call came from the Met for a last-minute replacement as Leonora. She said no, as she hadn't sung the part in four years, had no energy and didn't know the cuts, which had all been opened up. The Met responded, "You'll never work here or anywhere again if you don't do this," so Ross's second husband, another attorney, named Aaron Diamond, accepted the job while she was out of the apartment running an errand. She appeared that night. Maestro Patanè did not.

"I took it as much as I could and kept on going and going, and then in 1979, during a [Met] performance of Aida, I couldn't understand why I felt so strange. I woke up the next day with Bell's Palsy. So that was my final opera performance. I couldn't open my mouth for a couple of years. My voice was there — I had just started working on Isolde — but I couldn't open one side of my mouth. And I thought I looked like a cyclops. Subsequently, I had to have a big operation, with muscles taken out of my neck and put into the front of my face. I kept singing, though. I could do concerts out of town and got a lot of gigs in Asia. For a while I had a second home in Hong Kong and Taiwan. My son went to school there and stayed. So if somebody else would pay the car fare, I'd sing over there, so I could see Sonny Boy. He was fluent in Chinese, so he would often come along and introduce me. My Chinese was so bad that when I got one word right, they'd applaud!"

In spite of her age and some physical infirmities, Ross stays on the go. "I'm off to Spain with three lady friends. I do therapy twice a week. I think if I didn't exercise, I wouldn't be where I am today — it's not much, but I wouldn't like to have to be dependent on a wheelchair. Who knows? I couldn't walk at all a year ago. It's so slow-going, and I get impatient. But I keep going.

"A lot of people want me to teach, but that would drive me crazy. And people don't really know who I am, so who's going to come to me for coaching, anyway? Today when you coach, they don't want you to touch the voice. But I love coaching singers on roles I've done. I'm exacting. I want them to sing a beautiful vocal line. You work a note at a time, but no one seems to have the time to do that anymore. I guess that's why they come and go so fast. People don't understand the big voices. It goes in and out of fashion, especially the dramatic dark voice. Big voices need to learn how to float notes and to work the coloratura. What made me happiest about listening to that '67 Norma was my agility. Because I worked so hard on that."

When Ross finds it difficult to believe that the public remembers her, I assure her that fans are usually for life. And what would she like to tell them?

"Tell 'em I'm livin', baby — I'm breathin' out and in!"

SCOTT BARNES teaches masterclasses in Auditioning for Singers and Song Interpretation in New York City and abroad.

Foto: Dario Acosta

Maria Callas - A Exposição de Lisboa (II)

Ainda sobre a exposição que inaugura no próximo sábado vale a pena ler este artigo da Visão com mais alguns pormenores.

Wednesday, July 09, 2008

Maria Callas - A Exposição de Lisboa (I)

Recebi hoje a newsletter do S. Carlos que anuncia uma exposição comemorativa dos 50 anos da passagem de Maria Callas por Portugal (a famosa Traviata de Lisboa de 1958).

A exposição, em parceria com a EDP, terá lugar no Museu da Electricidade e estará patente ao público entre 12 de Julho e 21 de Setembro com entrada livre.

Diz na newsletter:

Da considerável colecção de jóias e 43 vestidos, destaca-se o traje de cena usado por Maria Callas na celebérrima Tosca encenada por Franco Zeffirelli que passou pelos palcos do Covent Garden, da Ópera de Paris e da Metropolitan Opera House de Nova Iorque. Dos adereços de cena e jóias em exposição, refira-se a coroa da Norma criada por Christian Dior para a produção estreada na Ópera de Paris em 1965.

A vasta documentação seleccionada inclui as últimas cartas de Maria Callas dirigidas a Aristóteles Onassis (por altura do romance com Jacqueline Kennedy), a Pier Paolo Pasolini e Maurice Béjart.

Para além da colecção de Bruno Tosi (Presidente da Associazione Internazionale «Maria Callas»), a exposição compreende um núcleo dedicado à produção da ópera La traviata protagonizada por Maria Callas, em 1958, no São Carlos. O cenário do Acto II é mostrado ao público pela primeira vez desde a estreia em 1958, para além de fotografias inéditas, recortes de Imprensa, o programa de sala autografado pela cantora e alguma da correspondência trocada entre Ansaloni, o agente milanês da Callas, e José de Figueiredo, director do São Carlos, responsável pela vinda de Maria Callas a Lisboa.

Mais informações em www.callaslisboa.com

A exposição, em parceria com a EDP, terá lugar no Museu da Electricidade e estará patente ao público entre 12 de Julho e 21 de Setembro com entrada livre.

Diz na newsletter:

Da considerável colecção de jóias e 43 vestidos, destaca-se o traje de cena usado por Maria Callas na celebérrima Tosca encenada por Franco Zeffirelli que passou pelos palcos do Covent Garden, da Ópera de Paris e da Metropolitan Opera House de Nova Iorque. Dos adereços de cena e jóias em exposição, refira-se a coroa da Norma criada por Christian Dior para a produção estreada na Ópera de Paris em 1965.

A vasta documentação seleccionada inclui as últimas cartas de Maria Callas dirigidas a Aristóteles Onassis (por altura do romance com Jacqueline Kennedy), a Pier Paolo Pasolini e Maurice Béjart.

Para além da colecção de Bruno Tosi (Presidente da Associazione Internazionale «Maria Callas»), a exposição compreende um núcleo dedicado à produção da ópera La traviata protagonizada por Maria Callas, em 1958, no São Carlos. O cenário do Acto II é mostrado ao público pela primeira vez desde a estreia em 1958, para além de fotografias inéditas, recortes de Imprensa, o programa de sala autografado pela cantora e alguma da correspondência trocada entre Ansaloni, o agente milanês da Callas, e José de Figueiredo, director do São Carlos, responsável pela vinda de Maria Callas a Lisboa.

Mais informações em www.callaslisboa.com

Tuesday, July 08, 2008

La Favorita - G. Donizetti - Cossotto; Kraus, Bruscantini, Raimondi; NHK Italian Opera Chorus, NHK Symphony Orchestra, de Fabritiis

Na Opera News deste mês de Julho, é dado destaque a uma gravação histórica reeditada em vídeo pela VAI em Novembro de 2007 da Ópera de Donizetti - La Favorita.

Na Opera News deste mês de Julho, é dado destaque a uma gravação histórica reeditada em vídeo pela VAI em Novembro de 2007 da Ópera de Donizetti - La Favorita.A gravação ocorreu em Tóquio em 1971 e conta com a participação de Fiorenza Cossotto (Leonora) e e de Alfredo Kraus (Fernando) nos principais papeis.

Curiosa a critica de Robert Baxter (Opera News) que começa por dizer que em 1971 o mundo da ópera era dominado pelos cantores e não por encenadores.

Transcrevo de seguida o texto de Robert Baxter na Opera News.

This Tokyo Favorita suffers from some serious blemishes, but anyone who can look past the dim video image and the dated staging will find much to admire.

The year is 1971. Singers — not the stage director — are the driving force in this production. And what singers! Fiorenza Cossotto (Leonora) and Alfredo Kraus (Fernando) are in their vocal prime. Together, they justify the purchase of this historic performance, taped in the Tokyo Bunka Kaikan. Sesto Bruscantini (Alfonso) and Ruggero Raimondi (Baldassare) add to the star power, enhanced by Oliviero de Fabritiis's seasoned conducting.

Visually, we're back in the operatic Dark Age. Stage director Bruno Nofri does little more than line up the chorus and shove the principals to the front of the stage, where they express dismay with hand on forehead or convey deep emotion by clutching their breast. Salvatore Russo's gorgeous costumes, delicately colored pastel, look lovely but suggest no specific time or place. When they can be seen, Enzo Dehò's dimly lit sets look imposing in a vaguely Spanish style.

The singers dominate this Favorita. The prolonged ovation — almost ten minutes of cheers and lusty applause — reflects the heat generated by these artists. Cossotto's brass-toned singing has scale and impact even when she lunges for high notes or plunges into chest voice. She offers a master class in the art of sustaining applause: after winning an ovation by banging out Leonora's "O mio Fernando" in brazen tones, she lowers her head and bats her eyes before placing hand on heart. Then, clasping her hands and smiling, she advances toward the audience.

Kraus, like the diva, provides a textbook performance — in vocal technique, not in milking applause. His tautly strung voice rises without effort to top C-sharp and flows with keen control through Donizetti's cantilena. He manages to suggest Fernando's transition from ardent lover to shamed hero and, joined by Cossotto in torrential voice, he rises to the testing demands of the long duet that crowns the opera. Urged on by de Fabritiis's incisive baton, the tenor and mezzo-soprano attack the music with fierce resolve and fill out the vocal lines with vibrant tone.

Bruscantini and Raimondi provide strong support but fail to reach this exalted level. Bruscantini almost compensates for his throaty tone with his solid musicianship and acting skills. Seizing center stage with his commanding presence, Raimondi sustains the music admirably even when his lightweight bass-baritone thins out in the lower reaches.

Monday, July 07, 2008

Norma - Teatro delle Muse di Ancona, 2004

Acaba de sair em CD, este registo de Norma de Vincenzo Bellini com o seguinte elenco:

Norma - Fiorenza Cedolins

Pollione - Vincenzo La Scola

Adalgisa - Carmela Remigio

Oroveso - Andrea Papi

Coro Lirico Marchigiano “Vincenzo Bellini”

Orchestra Filarmonica Marchigiana/Fabrizio Maria Carminati.

Leia aqui mais sobre este lançamento.

Norma - Fiorenza Cedolins

Pollione - Vincenzo La Scola

Adalgisa - Carmela Remigio

Oroveso - Andrea Papi

Coro Lirico Marchigiano “Vincenzo Bellini”

Orchestra Filarmonica Marchigiana/Fabrizio Maria Carminati.

Leia aqui mais sobre este lançamento.

Sunday, July 06, 2008

Joan Sutherland no programa This is your live - Austrália

Para os que são, como eu, admiradores incondicionais da voz e da carreira de Joan Sutherland, aqui ficam 3 vídeos com a participação da Diva no programa de televisão This is your live, gravado na Austrália durante os anos 70.

Thursday, September 06, 2007

Morreu o nosso Pavarotti

Soube há pouco que morreu o Pavarotti.

Outra grande voz que se cala para sempre.

A minha homenagem....

Viva o Pavarotti....

Outra grande voz que se cala para sempre.

A minha homenagem....

Viva o Pavarotti....

Wednesday, October 18, 2006

Fiorenza Cossotto

Recebi hoje a minha primeira Opera News. Em papel, pelo menos, uma vez que on-line se podem consultar todos os conteúdos.

De qualquer forma, folhear uma revista é sempre um prazer...

Gostei especialmente de um artigo relativo a uma das grande, se não a maior, Mezzo-soprano, do século XX. A GRANDE Fiorenza Cossotto.

Felizmente, tive a oportunidade, no ano passado, de ver e ouvir a senhora (sim, porque ainda não se retirou completamente), nos ensaios de um Trovador em Estremoz.

Assistir aos ensaios foi uma experiência inesquecível. A voz continua a ser a da Cossotto, com um pouco mais de "Vibratto".

Infelizmente, no dia da récita a Diva foi substituída devido a problemas de saúde.

Para os interessados, deixo o texto da Opera News.

Irene Minghini-Cattaneo ... Ebe Stignani ... Fedora Barbieri ... Giulietta Simionato ... Fiorenza Cossotto: these names evoke large personalities, and even larger voices. They are all members of a lineage, a great tradition — the Italian dramatic mezzo-soprano.

Although composers of opera had been creating roles for lower voices for hundreds of years, the type of big-voiced Italian mezzo typified by the artists listed above emerged only in the twentieth century, when the repertory in which they specialized became somewhat codified — the big-gun Verdi roles, with a sprinkling of bel canto and a few French heroines added to the mix — and the advent of recordings introduced this voice type to the world at large. Listening to these singers, one hears a consistency of approach — tonal opulence, ample volume, rapid vibrato and unbridled passion. (Even the sometimes-reserved Stignani cut loose as Verdi's Azucena).

Fiorenza Cossotto holds a special place in this tradition. She is not only a thrilling exponent — she is, at seventy-one, perhaps the last of the line. Once the still-singing mezzo wallops out her final curse on the priests of Egypt, or her last revelation to di Luna that Manrico is his brother, the curtain will be lowered on what seemed to be an unending era, with an unending supply of artists to fill this niche.

Cossotto herself cannot explain the current drought. "But, what would you like me to tell you?" the mezzo asked on the phone from her home in Crescentino, Vercelli. "It's a rare voice, because it is a voice that is not learned. The mezzo-soprano is born with the voice dark in the middle. When one tries to make the voice dark but is a short soprano, one is finished, because one tires in the middle and loses the high notes. Look, now, at my age, I am still singing — I still go on tour and do my concerts and operas. Last year I sang Amneris in Tokyo, and the most important critic wrote that the more I get on in years, the better I am. Why? Because this is the fruit of an entire life of study, eh?"

Cossotto's musical life began in her hometown, where she still resides. "A teacher heard me, and she heard that I had a voice different from the others, so she always had me do the solo parts. Later this teacher, who was a pianist, called my parents, because she wanted to advise that I be made to study singing. I went to the Torino Conservatory and did a sort of test. There were all the others, and we did a sort of contest, because there were so many of us but so few spots. And I won it and was admitted. In Italy the conservatory is public. I could not do it privately, because I didn't have the financial means. After five years I earned a degree in singing, and right away I did a contest to enter the school at La Scala. I won the contest and became a cadet at the La Scala school. After two months the school closed, and the most deserving ones were retained by the theater."

Cossotto made her La Scala debut in 1957, as Sister Mathilde in the world premiere of Poulenc's Dialogues of the Carmelites, which was sung in Italian. There followed a succession of small parts in which she made a big impression. Renata Scotto recalls, "She was doing small roles, and everybody loved her voice. When I made my debut as Amina [in La Sonnambula] I first met her. When I heard her first as Teresa in Sonnambula, I said, 'Oh my God! Where does this voice come from?' She had this melting, big sound — as Teresa!" Other roles at this time included the Madrigal Singer in Manon Lescaut, in which she was seen by the young bass Ivo Vinco, who courted the mezzo and married her a year later. In 1961, they had their only child, a son, Roberto. As well as Teresa to Callas's Amina, Cossotto sang Artemide to the great diva's Ifigenia in Tauride. The next few seasons brought Suzuki, Fenena (Nabucco), Marina, Hansel and Meg Page, among others. At this same time, her international career took off, with debuts in Wexford (1958, as Giovanna Seymour in Anna Bolena), Covent Garden (Neris in Medea with Callas) and Verona (Amneris, followed by Carmen and Azucena). Her U.S. debut, in Chicago in 1964 as Leonora in Donizetti's La Favorita, was a sensational success, and the young mezzo quickly skyrocketed to assume her place as the leading Italian dramatic mezzo. Engagements all over the world followed, and Cossotto began to build an enormous recorded legacy, which now encompasses a large catalogue of commercial recordings, augmented by many broadcasts and pirated performances available on CD and DVD.

The night of January 5, 1962, will always hold a special place in her heart, however, as it was the night of her Cinderella story on her home turf at La Scala. A revival production of La Favorita, mounted for Simionato, was suddenly without a star. "My lucky night arrived with Favorita. Simionato had become ill, precisely on opening night, and La Scala declared that it had never closed for any reason, and so they called me urgently, and I arrived there a quarter of an hour before the opening. They put the costumes on me, adjusted however they could, and I went on. I did well, because I came from a school like the Conservatorio di Torino, very prepared. I sang without mistakes, and it was my baptism in opera at La Scala! In the review the day after, from the Corriere della Sera, the greatest critic in Italy put a big headline — 'As of yesterday evening, a new star was born.' And from there I started my path in all theaters."

Cossotto's Metropolitan Opera debut, as Amneris, took place on February 6, 1968. By this time the voice was known in New York somewhat from recordings, but nothing could have prepared the public for the size, clarity and thrust of the instrument in the house. Donal Henahan in The New York Times praised not only her voice and skill as a singing actress but her "intelligence and restraint," the latter a characteristic associated less and less with this artist as time went on. The following season, when she first essayed Eboli at the Met, pandemonium ensued. One recalls that the power of Cossotto's voice seemed limitless, and the sheer volume and ease at both ends of the range were staggering, as was the no-holds-barred commitment. The middle register was warmer than it sounded in recordings; the heavy use of the "metal" in her tone, a feature emphasized at that time by the microphone, eventually pervaded her live singing, but not for some years. Allen Hughes in The New York Times reported that her veil song was "a tour de force of vocal and expressive virtuosity. Her voice is not really beautiful, but she can color it so variously as to make you feel it must be."

In the fall of 1970, she brought her Adalgisa to the Met, opposite Joan Sutherland's Norma, impressing observers with her fluid coloratura. This was not merely a huge voice but a sumptuous, well-schooled instrument. Just before that, the mezzo had sung her first New York Santuzza at the Met. Raymond Ericson of The New York Times wrote, "The voice is not so sensuous as it is strong, solid, and, at the top, brilliant. Miss Cossotto combines these resources into an intense portrayal of a desperate woman trapped in excommunication by the church. One pities her less than one is moved by the stubbornness, her fear, and her final tragedy." Harriet Johnson in The Post echoed Ericson's praise but added a warning: "Many mezzo-sopranos try Santuzza ... but only those who are vocally wiser than Miss Cossotto survive it over a period of time. She sang consistently loud and heavily. By overweighing her lower register, her high notes were strained."

Santuzza in the Met's Cavalleria Rusticana brings one to the subject of Franco Zeffirelli's association with the mezzo. Zeffirelli made his feelings about Cossotto public after she sang Adalgisa to Maria Callas's final Normas in 1964 and '65 in his Paris production, mounted for the diva. After those performances, Zeffirelli, feeling the young mezzo was insensitive to the veteran soprano's vocal frailties in their duets, swore he would never work with Cossotto again. (One wonders what might have taken place had a labor dispute — and resulting rescheduling — not prevented Cossotto's participation in the premiere of Zeffirelli's Met Cavalleria production in January 1970.)

The subject of the Callas episode is one for which Cossotto has little patience. "But look, it's a disgrace! It's been forty years, and books still come out speaking ill of me. The first year, we did our rehearsals, and everything went well. Callas was in good voice. There was no reason for her not to do Norma, which was her war-horse. During the last two performances [in 1965], she was not well — she had a cold, which passed down [into the chest]. The last performance, poor thing, she couldn't say no, because all of Onassis's elite was in the theater. But logically, she couldn't [sing], because she had already sung two performances on the cold. You don't play with Norma! In the [first] duet, it goes up to an A for the mezzo-soprano, and Callas must do the C. And the C didn't come out. When we got to the end of the duet, she could no longer do [here Cossotto sings the four ascending notes to the C]. But I couldn't hear this. I didn't know if she sang or didn't sing. I thought, it was better I sing my A calmly, so people won't notice, just in case. Instead, they started to say, 'Look, she sings when the other one doesn't sing anymore!' But, the other one didn't make a sound because she was ill — the voice didn't come out.

"Later, Callas, at the end of the second act, said to me, 'Fiorenza, stay tonight until the end, because I am not well, and we will all go out [to bow] together.' We'll make a bit of a good impression is what she wanted to say. 'Look,' I said, 'I can't, because I have to pack, since tomorrow morning I have to leave really early, but let's see.' My hotel was right next to the Opéra. I said, 'I'll manage. I'll go and come back right away.' If she had been angry with me, she wouldn't have said this. Is it true or not? But no one has ever published this! They have never said, 'Callas insisted that Cossotto be present at the end of the third act, that she go and thank the audience.' So, how does one explain this? If I had sung an extra note — something only idiots can assert — she wouldn't have said to me, 'Stay.' She would have been angry. From there it started. Even now, at a distance of forty years, they still speak ill of me. She wanted me the second year, wanted my presence. So, what is all this fantasy? They do it to enrich the books and the articles, and so they damage a person. I tried to help her onstage in every way. I have always been a serious colleague, not a colleague who does harm to people."

Fortunately, recordings of the final performance made by "pirates" in the audience have surfaced on CD, confirming Cossotto's version of the duet story. Callas omits her first exposed C, choosing a frequently used low alternate. Cossotto hits hers squarely and sustains it. When they reach the final cadenza, Callas manages a high B, with Cossotto a third below her on G. But ascending the scale at the end of the cadenza, Callas does not produce the C to complement Cossotto's high A, and the mezzo is left alone on the note. The audience responds very warmly, however, as they do all evening, encouraging the diva. Furthermore, in the subsequent duet, "Mira, o Norma," which Callas sings in a stunning sustained pianissimo, Cossotto seems to scale her voice down to match that of the ailing soprano.

Had Cossotto earned an unblemished reputation for herself as a colleague over the years, the Callas story would probably not have stuck. Sadly, this seems not to be the case. People in the business are reluctant to comment about her as a colleague on the record, preferring to praise her voice and suggest that she was difficult or ungenerous. Scotto, who worked with the mezzo from 1957 to 1993, takes a more circumspect, sympathetic view, chalking Cossotto's behavior up to a deep insecurity that produced a streak of competitiveness — and the need to be perfect. "Her part was always very well sung, because she had to be perfect. We grew up together artistically, and she was a great perfectionist, so that the conductor could say nothing about her musically. She would vocalize in the theater three hours before, singing the opera probably three times before she sings onstage. There were moments she made me angry, but I felt it was not done to show off — well, also she was showing off — but more for her inner person, because it was her character. If she had been another person, I believe she would have enjoyed this beautiful career more. I don't think she enjoyed it. And this is terrible."

Difficulties aside, Cossotto's has been a spectacular career of considerable duration. At the Met, she sang one hundred forty-eight performances between the seasons of 1967–68 and 1988–89. Her roles represented the core repertoire for her fach; in addition to those mentioned above, she essayed only five others — Azucena (which she more or less owned until Dolora Zajick arrived during her final season), Dalila and Carmen (the latter only on tour and in the parks concerts), a fiery Principessa in Adriana Lecouvreur and a stylish Mistress Quickly (which she added in 1985 at the spectacular debut of veteran Giuseppe Taddei). All of these were vivid, memorable interpretations. She has remained a star in starring roles, and her 1985 Amneris in the video of Leontyne Price's telecast farewell is as potent as it was at her debut.

There are, in fact, so many impressive audio and video documents of Cossotto's work that a discussion of them is impossible in this context, but one from a 1971 CBS Camera Three telecast perhaps best demonstrates the mezzo's prodigious gifts. Elegantly gowned, coiffed in the bouffant style of the era, Cossotto lets it rip in white-hot renditions of arias from Adriana Lecouvreur, Don Carlo and Cavalleria Rusticana. But in the middle of the program, she sings Neris's aria, "Solo un pianto," from Cherubini's Medea with utter refinement and a gentle outpouring of gorgeous tone. The rendition is devoid of any gutsy vocal mannerisms, entirely within the style. It is perfection and reflects great respect and seriousness of musical purpose.

In a 1983 OPERA NEWS interview, the mezzo attributed the onslaught of generic singing — and a seeming embarrassment on the part of young singers to cut loose emotionally — to the age of television and movie acting, as well as to the obsession with "a slender body dressed in a chic manner. It is a stylization that signifies nothing." She now adds, "The artist is born, and just as he was born in the 1800s, he's born in the 2000s. It's a question of sensibility. Also, there are no longer so many teachers. At one time we studied with the conductor for one month the phrasing, the way of speaking while singing. Now these things no longer exist. When I do master classes, I take care of, above all, that which singers no longer find: the mode of expression of the text, the color of the sound appropriate to a particular word. This is important! If I were a theater director, I would take on one, two artists of a certain age, who would teach all the young artists how one conveys a character, how a character lives onstage. Only by being near these greats can one learn."

Today, Cossotto is single, her marriage to Vinco having dissolved about ten years ago. "Some surprises jumped out" — she chuckles mischievously — "as can happen with so many couples. I am serene here at home. I do my work." Her work now consists of master classes, balanced with a more modest performing schedule. "Logically, I don't have the engagements as I did at one time, and therefore I squeeze in master classes in the various free periods." What roles does she still sing? "Roles like Eboli, Santuzza, it's logical that I can no longer tackle something like that — there are even [inherent] physical exertions. I still sing Trovatore, Aida, the Messa da Requiem. In other words, those less tiring." Less tiring? "Less tiring. And I added Ballo in Maschera to my repertoire, even if it's not really in my.…" she laughs heartily. "Well, it gives me much satisfaction, because I always have good reviews!"

IRA SIFF is a New York-based voice and interpretation teacher and stage director for opera. He performs as "traumatic soprano" Madame Vera Galupe-Borszkh.

De qualquer forma, folhear uma revista é sempre um prazer...

Gostei especialmente de um artigo relativo a uma das grande, se não a maior, Mezzo-soprano, do século XX. A GRANDE Fiorenza Cossotto.

Felizmente, tive a oportunidade, no ano passado, de ver e ouvir a senhora (sim, porque ainda não se retirou completamente), nos ensaios de um Trovador em Estremoz.

Assistir aos ensaios foi uma experiência inesquecível. A voz continua a ser a da Cossotto, com um pouco mais de "Vibratto".

Infelizmente, no dia da récita a Diva foi substituída devido a problemas de saúde.

Para os interessados, deixo o texto da Opera News.

Irene Minghini-Cattaneo ... Ebe Stignani ... Fedora Barbieri ... Giulietta Simionato ... Fiorenza Cossotto: these names evoke large personalities, and even larger voices. They are all members of a lineage, a great tradition — the Italian dramatic mezzo-soprano.

Although composers of opera had been creating roles for lower voices for hundreds of years, the type of big-voiced Italian mezzo typified by the artists listed above emerged only in the twentieth century, when the repertory in which they specialized became somewhat codified — the big-gun Verdi roles, with a sprinkling of bel canto and a few French heroines added to the mix — and the advent of recordings introduced this voice type to the world at large. Listening to these singers, one hears a consistency of approach — tonal opulence, ample volume, rapid vibrato and unbridled passion. (Even the sometimes-reserved Stignani cut loose as Verdi's Azucena).

Fiorenza Cossotto holds a special place in this tradition. She is not only a thrilling exponent — she is, at seventy-one, perhaps the last of the line. Once the still-singing mezzo wallops out her final curse on the priests of Egypt, or her last revelation to di Luna that Manrico is his brother, the curtain will be lowered on what seemed to be an unending era, with an unending supply of artists to fill this niche.

Cossotto herself cannot explain the current drought. "But, what would you like me to tell you?" the mezzo asked on the phone from her home in Crescentino, Vercelli. "It's a rare voice, because it is a voice that is not learned. The mezzo-soprano is born with the voice dark in the middle. When one tries to make the voice dark but is a short soprano, one is finished, because one tires in the middle and loses the high notes. Look, now, at my age, I am still singing — I still go on tour and do my concerts and operas. Last year I sang Amneris in Tokyo, and the most important critic wrote that the more I get on in years, the better I am. Why? Because this is the fruit of an entire life of study, eh?"

Cossotto's musical life began in her hometown, where she still resides. "A teacher heard me, and she heard that I had a voice different from the others, so she always had me do the solo parts. Later this teacher, who was a pianist, called my parents, because she wanted to advise that I be made to study singing. I went to the Torino Conservatory and did a sort of test. There were all the others, and we did a sort of contest, because there were so many of us but so few spots. And I won it and was admitted. In Italy the conservatory is public. I could not do it privately, because I didn't have the financial means. After five years I earned a degree in singing, and right away I did a contest to enter the school at La Scala. I won the contest and became a cadet at the La Scala school. After two months the school closed, and the most deserving ones were retained by the theater."

| |

© Johannes Ifkovits 2006 | |

The night of January 5, 1962, will always hold a special place in her heart, however, as it was the night of her Cinderella story on her home turf at La Scala. A revival production of La Favorita, mounted for Simionato, was suddenly without a star. "My lucky night arrived with Favorita. Simionato had become ill, precisely on opening night, and La Scala declared that it had never closed for any reason, and so they called me urgently, and I arrived there a quarter of an hour before the opening. They put the costumes on me, adjusted however they could, and I went on. I did well, because I came from a school like the Conservatorio di Torino, very prepared. I sang without mistakes, and it was my baptism in opera at La Scala! In the review the day after, from the Corriere della Sera, the greatest critic in Italy put a big headline — 'As of yesterday evening, a new star was born.' And from there I started my path in all theaters."

Cossotto's Metropolitan Opera debut, as Amneris, took place on February 6, 1968. By this time the voice was known in New York somewhat from recordings, but nothing could have prepared the public for the size, clarity and thrust of the instrument in the house. Donal Henahan in The New York Times praised not only her voice and skill as a singing actress but her "intelligence and restraint," the latter a characteristic associated less and less with this artist as time went on. The following season, when she first essayed Eboli at the Met, pandemonium ensued. One recalls that the power of Cossotto's voice seemed limitless, and the sheer volume and ease at both ends of the range were staggering, as was the no-holds-barred commitment. The middle register was warmer than it sounded in recordings; the heavy use of the "metal" in her tone, a feature emphasized at that time by the microphone, eventually pervaded her live singing, but not for some years. Allen Hughes in The New York Times reported that her veil song was "a tour de force of vocal and expressive virtuosity. Her voice is not really beautiful, but she can color it so variously as to make you feel it must be."

In the fall of 1970, she brought her Adalgisa to the Met, opposite Joan Sutherland's Norma, impressing observers with her fluid coloratura. This was not merely a huge voice but a sumptuous, well-schooled instrument. Just before that, the mezzo had sung her first New York Santuzza at the Met. Raymond Ericson of The New York Times wrote, "The voice is not so sensuous as it is strong, solid, and, at the top, brilliant. Miss Cossotto combines these resources into an intense portrayal of a desperate woman trapped in excommunication by the church. One pities her less than one is moved by the stubbornness, her fear, and her final tragedy." Harriet Johnson in The Post echoed Ericson's praise but added a warning: "Many mezzo-sopranos try Santuzza ... but only those who are vocally wiser than Miss Cossotto survive it over a period of time. She sang consistently loud and heavily. By overweighing her lower register, her high notes were strained."

Santuzza in the Met's Cavalleria Rusticana brings one to the subject of Franco Zeffirelli's association with the mezzo. Zeffirelli made his feelings about Cossotto public after she sang Adalgisa to Maria Callas's final Normas in 1964 and '65 in his Paris production, mounted for the diva. After those performances, Zeffirelli, feeling the young mezzo was insensitive to the veteran soprano's vocal frailties in their duets, swore he would never work with Cossotto again. (One wonders what might have taken place had a labor dispute — and resulting rescheduling — not prevented Cossotto's participation in the premiere of Zeffirelli's Met Cavalleria production in January 1970.)

The subject of the Callas episode is one for which Cossotto has little patience. "But look, it's a disgrace! It's been forty years, and books still come out speaking ill of me. The first year, we did our rehearsals, and everything went well. Callas was in good voice. There was no reason for her not to do Norma, which was her war-horse. During the last two performances [in 1965], she was not well — she had a cold, which passed down [into the chest]. The last performance, poor thing, she couldn't say no, because all of Onassis's elite was in the theater. But logically, she couldn't [sing], because she had already sung two performances on the cold. You don't play with Norma! In the [first] duet, it goes up to an A for the mezzo-soprano, and Callas must do the C. And the C didn't come out. When we got to the end of the duet, she could no longer do [here Cossotto sings the four ascending notes to the C]. But I couldn't hear this. I didn't know if she sang or didn't sing. I thought, it was better I sing my A calmly, so people won't notice, just in case. Instead, they started to say, 'Look, she sings when the other one doesn't sing anymore!' But, the other one didn't make a sound because she was ill — the voice didn't come out.

"Later, Callas, at the end of the second act, said to me, 'Fiorenza, stay tonight until the end, because I am not well, and we will all go out [to bow] together.' We'll make a bit of a good impression is what she wanted to say. 'Look,' I said, 'I can't, because I have to pack, since tomorrow morning I have to leave really early, but let's see.' My hotel was right next to the Opéra. I said, 'I'll manage. I'll go and come back right away.' If she had been angry with me, she wouldn't have said this. Is it true or not? But no one has ever published this! They have never said, 'Callas insisted that Cossotto be present at the end of the third act, that she go and thank the audience.' So, how does one explain this? If I had sung an extra note — something only idiots can assert — she wouldn't have said to me, 'Stay.' She would have been angry. From there it started. Even now, at a distance of forty years, they still speak ill of me. She wanted me the second year, wanted my presence. So, what is all this fantasy? They do it to enrich the books and the articles, and so they damage a person. I tried to help her onstage in every way. I have always been a serious colleague, not a colleague who does harm to people."

Fortunately, recordings of the final performance made by "pirates" in the audience have surfaced on CD, confirming Cossotto's version of the duet story. Callas omits her first exposed C, choosing a frequently used low alternate. Cossotto hits hers squarely and sustains it. When they reach the final cadenza, Callas manages a high B, with Cossotto a third below her on G. But ascending the scale at the end of the cadenza, Callas does not produce the C to complement Cossotto's high A, and the mezzo is left alone on the note. The audience responds very warmly, however, as they do all evening, encouraging the diva. Furthermore, in the subsequent duet, "Mira, o Norma," which Callas sings in a stunning sustained pianissimo, Cossotto seems to scale her voice down to match that of the ailing soprano.

| |

In 1968 with her then-husband, bass Ivo Vinco © Erika Davidson 2006 | |

Difficulties aside, Cossotto's has been a spectacular career of considerable duration. At the Met, she sang one hundred forty-eight performances between the seasons of 1967–68 and 1988–89. Her roles represented the core repertoire for her fach; in addition to those mentioned above, she essayed only five others — Azucena (which she more or less owned until Dolora Zajick arrived during her final season), Dalila and Carmen (the latter only on tour and in the parks concerts), a fiery Principessa in Adriana Lecouvreur and a stylish Mistress Quickly (which she added in 1985 at the spectacular debut of veteran Giuseppe Taddei). All of these were vivid, memorable interpretations. She has remained a star in starring roles, and her 1985 Amneris in the video of Leontyne Price's telecast farewell is as potent as it was at her debut.

There are, in fact, so many impressive audio and video documents of Cossotto's work that a discussion of them is impossible in this context, but one from a 1971 CBS Camera Three telecast perhaps best demonstrates the mezzo's prodigious gifts. Elegantly gowned, coiffed in the bouffant style of the era, Cossotto lets it rip in white-hot renditions of arias from Adriana Lecouvreur, Don Carlo and Cavalleria Rusticana. But in the middle of the program, she sings Neris's aria, "Solo un pianto," from Cherubini's Medea with utter refinement and a gentle outpouring of gorgeous tone. The rendition is devoid of any gutsy vocal mannerisms, entirely within the style. It is perfection and reflects great respect and seriousness of musical purpose.

| |

Azucena to Robert Merrill’s di Luna in Il Trovatore at the Met, 1973 © Beth Bergman 2006 | |

Today, Cossotto is single, her marriage to Vinco having dissolved about ten years ago. "Some surprises jumped out" — she chuckles mischievously — "as can happen with so many couples. I am serene here at home. I do my work." Her work now consists of master classes, balanced with a more modest performing schedule. "Logically, I don't have the engagements as I did at one time, and therefore I squeeze in master classes in the various free periods." What roles does she still sing? "Roles like Eboli, Santuzza, it's logical that I can no longer tackle something like that — there are even [inherent] physical exertions. I still sing Trovatore, Aida, the Messa da Requiem. In other words, those less tiring." Less tiring? "Less tiring. And I added Ballo in Maschera to my repertoire, even if it's not really in my.…" she laughs heartily. "Well, it gives me much satisfaction, because I always have good reviews!"

IRA SIFF is a New York-based voice and interpretation teacher and stage director for opera. He performs as "traumatic soprano" Madame Vera Galupe-Borszkh.

Tuesday, October 17, 2006

Lawrence Brownlee

Vi este nome num comentário a um vídeo com o Juan Diego Floréz em www.youtube.com.

Por curiosidade consultei um site na Internet sobre este intérprete.

Não vejo a hora de o ouvir.

Já agora quem estiver interessado pode consultar a página ofícial do tenor em http://www.lawrencebrownlee.com/.

Por curiosidade consultei um site na Internet sobre este intérprete.

Não vejo a hora de o ouvir.

Já agora quem estiver interessado pode consultar a página ofícial do tenor em http://www.lawrencebrownlee.com/.

Wednesday, August 09, 2006

Juan Diego Flórez volta a brilhar

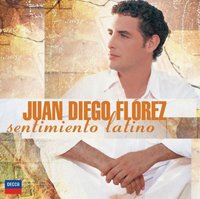

O Tenor Juan Diego Flórez famosissímo nas suas interpretações em óperas de Rossini, Bellini e Donizetti, faz agora o um "semi-crossover" com o seu novo trabalho de nome "Sentimiento Latino".

O Tenor Juan Diego Flórez famosissímo nas suas interpretações em óperas de Rossini, Bellini e Donizetti, faz agora o um "semi-crossover" com o seu novo trabalho de nome "Sentimiento Latino".Estou curioso com esta nova abordagem se bem que deteste "crossovers".

Trancrevo a critica de IRA SIFF, publicada na Opera News em Maio passado.

Tenor Juan Diego Flórez, known primarily for his prodigious gift with florid music, takes a semi-crossover turn here, singing early- to mid-twentieth-century songs by Latin American and Spanish composers. The material lends itself perfectly to the operatic voice, and Flórez, with his sunny tone and bravado high notes, clearly has a great time putting it across.

The disc opens with an exciting arrangement of Pedro Elías Gutiérrez’s “Alma llanera” from a 1914 zarzuela. Flórez, very much a tenor, crowns it with a terrific high C. A contrast in mood follows immediately, with a wonderful melancholy waltz, “Ella,” by Mexican composer José Alfredo Jiménez. María Isabel Granda Larco, a prominent Peruvian singer/songwriter who was known as “Chabuca Granda,” is represented with three songs, all arranged by Flórez, who grew up admiring her work. The evocative “La flor de la canela” and “Bello durmiente” are both lovely. “Fina estampa” is accompanied only by guitar (David Gálvez) and bongos (Flórez) and offers a pleasant contrast to the arrangements and orchestrations (mostly by Ángel “Cucco” Peña) on the rest of the disc, which are marvelous — rhythmically contagious, with wonderful trumpet and string licks.

One can never have too many recordings of Agustín Lara’s “Granada,” committed to disc by everyone from Mario Lanza to Fritz Wunderlich (in one of his most thrilling recordings), and Flórez’s spirited rendition is most welcome. José Sancho Padilla’s tender “Princesita” was a favorite of Tito Schipa, and here Flórez offers a dynamic modulation and sweetness one expects from his voice type but doesn’t always find in his onstage work.

Flórez also wisely opts to include little-known chestnuts like María Grever's "Júrame," a gorgeously sweeping, dramatic, operetta-style melody. Also operatic in scope is “Siboney,” by the beloved Cuban pianist/composer, Ernesto Lecuona. Closing the disc is “México lindo,” a thrilling, driving ode to the homeland of its composer, Chucho Monge, crowned here by another of the tenor’s sensational high Cs. Led by Miguel Harth-Bedoya, the Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra, the Mariachi de Oro and numerous instrumental soloists all lend excellent support and splendid playing.

IRA SIFF

Alberto Grilo

Tuesday, August 08, 2006

Opera News

Resolvi voltar a assinar a Opera News. Embora considere a revista um pouco "americanizada", não temos na Europa nenhuma a preços tão acessíveis. Além de que a ediação on-line é bastante útil.

Alberto Velez Grilo

Alberto Velez Grilo

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)